Too many seek refuge in propaganda that what is being done to Palestinians is necessary.

Egyptian-born Omar El Akkad had studied in the United States and been 10 years a journalist when, in the summer of 2021, he became an American citizen. Covering the War on Terror in Afghanistan and at the U.S. detention center in Guantanamo Bay exposed him to the “deep ugly cracks in the bedrock of this thing they called “the free world.” Yet he believed the cracks could be repaired – “Until the fall of 2023. Until the slaughter.”

The slaughter was Israel’s razing of Gaza following Hamas’s rampage into Israel on October 7, 2023. The Israeli assault escalated to include massive bombardment, enforced hunger, destruction of hospitals and schools, bulldozing of dwellings deprivation of medical care, torture and the slaughter of tens of thousands of men, women and children. The onslaught caused Akkad to despair for Gaza’s Palestinians and for his adopted country, whose financing and weapons enabled it. He channelled that despair into the rage that inspired this excellent and troubling book.

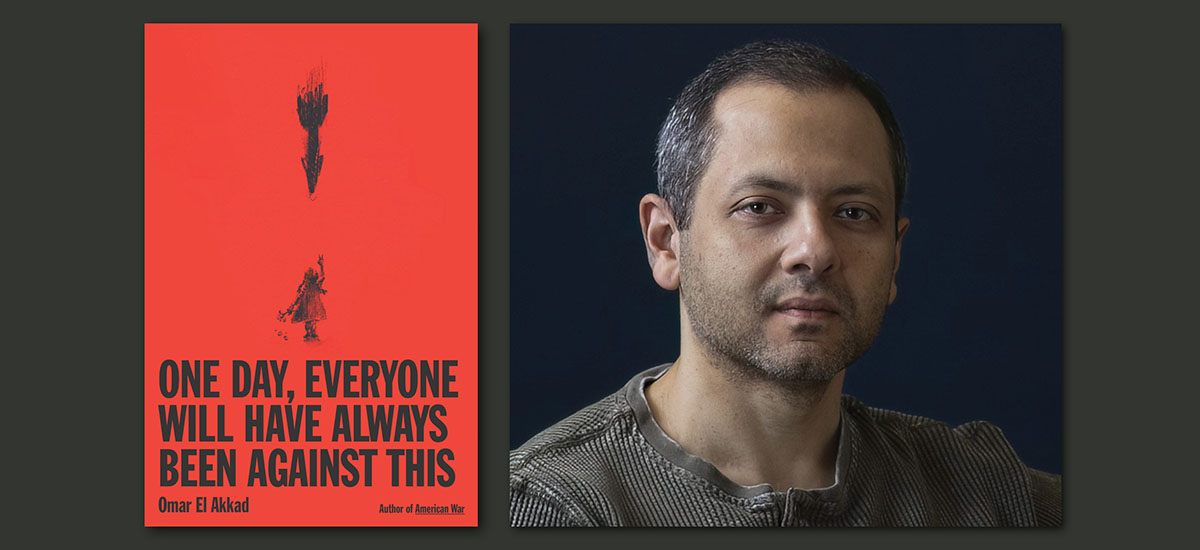

One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This is neither polemic nor memoir, although it contains elements of both. Akkad’s prose is an appeal to readers not to wait for “one day” in the distant future to resist injustice not only in Gaza, but in the wider world: “In the coming years there will be much written about what took place in Gaza, the horrors that have been meticulously documented by Palestinians as they happened and meticulously brushed aside by the major media apparatus of the western world.” When the killing ceases, as with genocides of native Americans, Tasmanians, Namibia’s Hereros and Namas, Armenians, Jews and Tutsis, it will be too late.

Continue reading →